Peter Heather Fall of the Roman Empire Review

Book review — Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Nativity of Europe by Peter Heather

Peter Heather'south volume is very enjoyable if you really relish history. And it is a serious history rather than a popular history book. I love pop history books, but Empires and Barbarians is the sort of history volume that challenges received wisdom and argues its case forcefully rather than just being a fun chronological history or arguing that Brexit Is Just Like The Break Up Of Austo-Republic of hungary Or Whatever. Taking in eleven lengthy capacity, this book is a thorough look at how the diverse tribes of Rome'southward barbaricum ultimately destroyed Rome and reshaped Europe into a patchwork of states which, if yous squint, are pretty plain the precursor states of today's Europe. [one]

And what a transformation it was. Until the quaternary century Rome reached deep into northern Europe, by the 5th century the western empire was gone and barbarians were forming kingdoms beyond one-time Roman territory. The suddenness of this change belies a procedure that had roots hundreds of years before (and hundreds of miles away) and which would continue operating for hundreds of years more uniting a continent from the Atlantic to the Volga, and the Baltic to the Mediterranean. All in only a grand years. That's relatively speedy, all things considered. The real force of Heather's book is approaching this question without an end betoken in listen, without a teleological approach equally we say in the biz, and his reliance on comparative migration studies to inform how and why people moved. Comparisons with Boer Voortrekkers or Rwandans fleeing into the Congo in a book about the Visigoths could expect out of identify, but are deployed well to bolster his case.

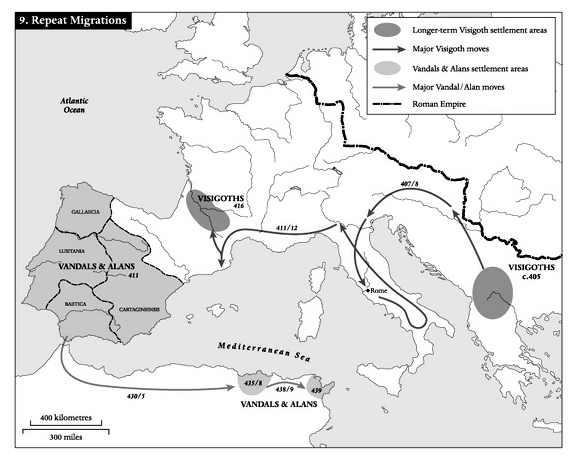

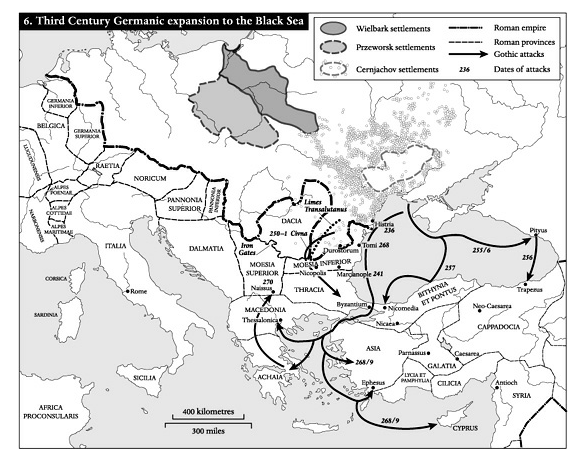

The central argument is that development and migration are intimately linked. This is widely accustomed now and its unsurprising that this was true in the past, but Heather does a practiced job of describing how subtle differences in evolution impact the forms and flows of migration. For example, at the beginning of the Viking era Denmark had a stable monarchy; its relative poverty compared to Britain and Carolingian Europe induced Viking raiding parties to go out, their subsequent render with wealth was transformed into a fighting forcefulness which ultimately destabilised the monarchy. The interaction of migration and evolution continued though and the political fragmentation only lasted until local resistance to Viking raiding parties improved. This lead to the Nifty Armies phase of Viking conquest as fragmentation and modest scale raids are s replaced past larger scale assaults, with warriors numbering in the 10,000s rather than 100s. Similar patterns are appreciable in the Roman Cadre/Periphery/Semi-periphery, in the movements of the Ostrogoths to Italy, Vandals and Alans in Espana and North Africa, Anglo-Saxons in England.

To reach Greenland, plough left at the middle of Norway, go on so far north of Shetland that you tin can only see it if the visibility is very good, and far enough due south of the Faroes that the ocean appears half style upwardly the mountain slopes. As for Iceland, stay and then far to the south that you only run into its flocks of birds and whales.

Viking directions to Greenland

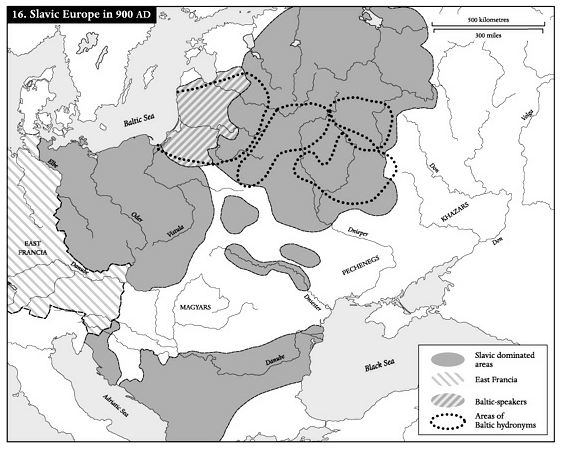

Peculiarly intriguing is his description of how the collapse of the Hunnic Empire ultimately caused such chaos that people faced no better choice just to invade Rome. The Huns weren't Romes straight neighbours, and the historical sources effectually the illiterate nomads are pretty poor, but they established a loose empire in fundamental Europe away from Rome's centre of ability. Attila'southward death threw dominance to whoever could grab information technology and led to widespread destruction and death. That collection people due west, towards the wealth and relative stability of 5th century Rome. Ane question asked is, if Attila had been amend at succession planning would Rome take fallen when information technology did? Indeed, this leads to another question, if the exodus of armed men from Germanic Europe into old Roman grounds had non occurred on such a grand scale could Slavs have later moved in and go the dominant group of Eastern Europe? Europe without widespread Slavic settlement is about impossible to imagine, but it could have happened. [2]

One of the books strengths is its rejection of Marxist interpretations of what happened in Europe in this menses. The book is very materialist and certainly it argues that material factors impact behaviours and outcomes, but the simplistic slavery and manoralism and bullwork and modernity schema of vulgar Marxist development theory is absent, and widely mocked. Then too is the sometime idea of "peoples" made up of men, women, children and the elderly flooding over Roman frontiers, bringing down the empire and mostly milling around Europe. This idea has been out of style academically for a long time since information technology was pop with 19th century nationalists. Merely Heather besides skewers those who go to far the other mode and imply there was no migration and that people just upped and inverse culture occasionally without whatsoever migratory influence.

Another great aspect of the book is the whimsical asides. Existence a historian of this period is not easy, the sources as bad, the archaeology ambiguous, the debates are thus viscous and and then Heather'south good-natured arroyo is welcome. On dealing with gaping holes in the evidence on the gender residual after a menses of migration we are met with this:

Nothing indicates, for example, that they formed a numerical majority of the male population; and given their plain privileged position, I would be willing to bet quite a lot of coin that they did non.

This is how historical argument should be done! And "the then-chosen Gallic Chronicle of 452 (so called in a fit of wild scholarly fancy because information technology was put together in Gaul in 452)" gives the impression of an writer who loves his subject, including its funny piddling ways. Likewise he sums upwards the benefits of studying the Carolingian Empire thusly: "Those who study the first millennium AD have a singled-out advantage when it comes to the historic period-onetime game of Name Five Famous Belgians." There are several more, each i amusing enough on its own but likewise building a movie of an writer who not only really knows his stuff but too really enjoys his work, down to the fact the Vikings sacked Lindisfarne on his birthday.

One criticism of this volume is the lack of anyone but men in information technology. The historical and archaeological sources for women and children in the period are limited, but its a pity what is there isn't engaged with more than. The only time women characteristic prominently is when discussing precisely who the Vikings were marrying. In this DNA evidence from Republic of iceland suggests Vikings were picking up wives along the mode (some relatively peacefully, simply more likely not). Sexual violence is ever present, but rarely touched upon in any detail. Also DNA evidence is sparingly used in the text, and an updated one bringing more upward-to-date information could help inform more of the darker areas of the offset millennia timeline.

That said I withal think this is an excellent book because it humanises the barbarians of Europe. By presenting things through the lens of comparative migrations this volume makes it much easier to understand why and how it seemed like a skillful idea for Theodoric the Amal to spend years leading the Visigoths up and down the Balkan peninsula, sack Rome and settle in southwest Gaul. The mixture of political push and economic pull is recognisable to anybody, and past showing the blueprint repeating and the conditions required Heather brings us closer to seeing our ancestors equally much more similar us than we sometimes imagine. His description of why people moved besides answers the other question implied, why they stopped. They stopped because economical development shepherded early state formation to the point where people would adopt to stand and fight than run abroad; and that rootedness too is too piece of cake to understand with.

[1] I've already mentioned this book here when I reflected on the changing face of nationalist academics.

[ii] As well, spring winds brought Vikings to Great United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland and in fall the winds reversed and brought them home to shelter over winter. If trade winds had been the other way circular would Picts accept been raiding the Vikings? If

Source: https://medium.com/@leftoutside/book-review-empires-and-barbarians-the-fall-of-rome-and-the-birth-of-europe-by-peter-heather-4381adb6175e

0 Response to "Peter Heather Fall of the Roman Empire Review"

Post a Comment